Dr Kevin Wang

TLC for veggies

Imagine having little sensors buried around your market garden telling you at 15-minute intervals what the soil’s moisture content and temperature readings were.

The readings could be automatically sent to you anywhere in the world via long-range wireless using the Internet of Things (IoT) and the Cloud. You’d know exactly when to irrigate and where, down to 3 to 5 m blocks, and you’d also be able to crunch the data, rate yield against conditions and soon know exactly what combinations would give you the flavours and cropping volumes you were looking for.

It would work for vineyards and market gardeners – in fact any application where soil temperature and moisture content are critical.

Science for Technological Innovation National Science Challenge (SfTI) researcher Dr Kevin Wang of the University of Auckland has used SfTI Seed research funding to trial a new underground wireless data acquisition system.

Using a unique low power wide area network system (LPWAN), Kevin’s been able to successfully transmit data from sensors buried up to 50 cm in the earth to on-farm data hubs that can then leapfrog the data into the Cloud and on to anywhere.

He says he and his team Akshat Bisht and Shiyang Wu have been limited more by gardening implements than technology.

Using a manual earth auger's a lot of work

“We’ve only been able to bury the sensors at 50cm deep mainly because we were using a manual earth auger during the experiment and it’s a lot of work to go any deeper.”

The results so far have been very promising, with the probe sensors linked to a coin-sized device encased in a water-proof plastic casing.

The LPWAN system allows tiny amounts of data to travel a long way – kilometres, rather than just a few metres with a traditional wireless set up.

“The data for temperature and moisture readings is in very small packets, so that’s all you need,” Kevin says.

“If you used a traditional wireless set up, it would only be good for very short range, so you’d need a lot of data hubs with internet access to get measurements right across the farm.”

Existing solutions are already in operation around the world but are costly and most have to be read manually.

“Our trial saves the farmer having to deploy someone to go out and take a reading and also gives a much better resolution with sensors laid out even 3 to 5 m apart, rather than a few per hectare. You’d be able to design your irrigation to avoid over and under watering and reduce the problem of nutrients disappearing into the waterways.”

Kevin says there are a few more problems to work through.

“The next steps would be to optimise battery life. The units run on two AA batteries for between 3 and 6 months, but we think we can improve on that to run multiple years on smaller coin cell batteries.”

The other issue is knowing exactly where the units are in the ground.

Nobody wants 400 flags sticking up in their veggie patch

For the trial, the team used flags on sticks to locate the sensors, but nobody wants 400 flags sticking up in their veggie patch. Putting GPS technology into them all would send the cost per unit through the roof.

Challenges aside, the science has worked very well.

“We’re very happy with what we’ve been able to show so far. In fact, the only reading failure during the whole trial turned out to be a fault with the sensors itself – not the tech!”

Congratulations on your research achievement Kevin!

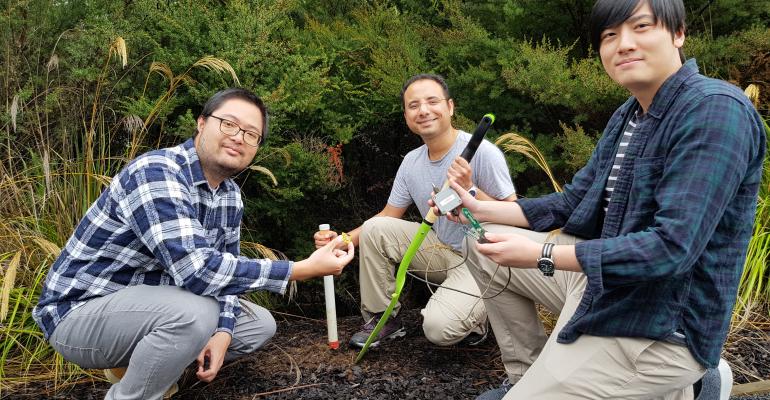

Top image: SfTI researcher Kevin Wang (left) holds the unique LPWAN device, fellow researcher Akshat Bisht holds one of the installation sticks, and student Sean Wu holds a sensor.